NO PAINTING SUMS UP the alienation and isolation of 21st century existence as does The Scream by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch. After Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, it is the second most recognised painting in the world.

The idea came to Munch while walking in the wooded hills above old Oslo more than a century ago, following a bout of heavy drinking the previous evening.

“I was walking along the road with two friends. The sun set. I felt a great sadness. Suddenly the sky became blood red. I stopped, leaned against the railings, dead tired. And saw the flaming clouds as blood over the blue-black fjord and city. My friends walked on. I stood there trembling with angst. And I sensed a loud, unending scream pierce nature.”

Written shortly after his walk, the words that would eventually lead to the series of paintings and lithographs entitled Skrik (The Scream), contain the sense of inner anguish conveyed by the lone figure standing beneath a turbulent sunset; his eyes and mouth wide open, hands clamped to bulging temples.

One fine morning with a clear head, and without the paranoia of a heavy hangover, I set out to retrace Munch’s footsteps. The number 19 tram trundles eastwards through Oslo city centre up into the woods that form part of Ekeberg Park, a popular spot for Sunday strollers. Munch lived nearby for a time and often walked through the park. I alighted at Sjømannsskolen (The Seaman’s School).

There were no signposts indicating the artistic importance of the site but, knowing the area, I crossed the road to enter the grounds of the business training centre now occupying the former Seaman’s School. Coincidentally, some of the oldest known examples of art in Norway lie carved into a granite rock to the left of the entrance. Even after 6,000 years of harsh northern climes it is still possible to discern the worn outlines of deer and elk picked out in red. Munch’s famous view lies to the rear of the building.

Armed with a copy of the The Scream, gazing down at the magnificent view of the city, it is possible to work out where Munch must have paused that day, more or less. A small path below the school leads down a grassy slope to a rail reminiscent of the one in the painting. But that doesn’t quite fit. There is another more likely candidate below. A little nearer to the shore of the fjord, it becomes clear the rutted track the artist portrayed over a century before has transformed into a busy highway leading to Sweden.

The several versions of The Scream Munch painted were never intended to depict reality, but to represent his tortured state of mind. Munch made a point of painting from memory. On such a fine morning it is difficult to feel the terrible angst that seized him.

From this point Oslo spreads out below as a three-dimensional map. Far on the other side of the city the scimitar shape of Holmenkollen stands near the top of surrounding hills. Built for the 1952 Winter Olympics the ski jump has become one of several iconic symbols of the city. Looking down, hugging the far side of the fjord, two steeply pitched roofs stand out. These are the museums housing the Kon Tiki and Fridtjof Nansen’s polar ship Fram – each a reminder of Norway’s strong maritime history. The magnificent Viking ships Gokstad and Oseberg are housed there too, all near Bygdøy outdoor Folk Museum.

To the right, nearer the fjord’s apex, stands an impressive red-brick structure. Bauhaus in feeling, two towering cubist towers mark it out as Rådhus, the City Hall. The impressive building was completed just before World War II. Munch harboured an unfulfilled ambition to decorate the interior walls with a frieze.

Edvard Munch

On the peninsula jutting out in the foreground of Rådhus stands Akerhus fortress, built to defend the city against attack. Munch’s father, Dr Christian Munch, took up the post of army corps physician there in 1864, the year following Edvard’s birth.

I walk out of the business school grounds, and across the tram lines, into Ekeberg Park. A signpost marked Jernalderstien leads me through the woods to the first path on the left, and back down into the city. Built in 1929, and well worth seeing, Ekeberg Restaurant is a fine, early example of functionalist architecture. At a fork marked by two log benches, it is time to turn left. The winding path gets steeper here, and is quite rough in places. Finally, I emerge at Oslo Gate, on the eastern edge of the old town.

There are some medieval ruins here worth seeing before Oslo Gate leads into Grønlandsleiret. Not so long ago this area was completely run down. However, an influx of immigrants from the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East in the Seventies and Eighties brought about a transformation. Their influence and industry has helped regenerate the locality. They opened new businesses and brought fresh life to the area. When the potential of its elegant and spacious 19th century flats was rediscovered in the 1990s, things change even further. Grønland has become home to a broad mix of society with ethnic shops, cafes and restaurants rubbing shoulders with fashionable bars and design studios.

Set in a leafy park is Oslo’s oldest prison. I spent the night of November 2nd 1999 in a cell there, courtesy of Oslo’s police. There had been a violent demonstration against the visit of Bill Clinton, which I had followed in my role as a freelance journalist. Taking photos of police brutality right in the thick of the crowds had obviously rubbed a few officers up the wrong way. But my spirits were lifted upon release to see a crowd of teenage girls huddled under a tree in the pouring rain. Clapping and cheering me like a hero, they’d been waiting there all night. When I told them I’d only been arrested by mistake, they said it didn’t matter, I’d been arrested, and that was good enough for them.

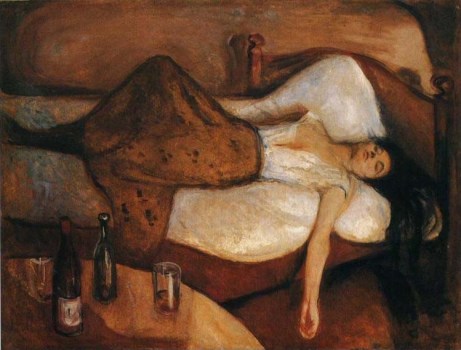

The Day After 1895 Oil on canvas

At the other end of Grønland lies Vaterland Bridge. It’s a long time since Lilletorvet, the market Munch drew in 1881 disappeared. Yet the empty spaces beneath the flyover cry out for it to be brought back. I make my way towards a towering glass and steel hotel where tall. stark and ugly concrete structures overwhelm the essential provinciality of the city. Beyond this alienating urban wasteland, only the old façade of Central Station remains in a pathetic attempt to conceal the grave architectural travesty committed in the name of progress. For here begins Karl Johan’s Gate, Oslo’s most famous thoroughfare. Named after an 18th century king, it was home to Norway’s thriving artistic community in Munch’s day.

As well as featuring in many of Munch’s works, the street played a central role in his life. A little way up, I turn left into Nedre Slottsgata. Opposite Steen & Strøm department store is number 9. This was Munch’s first address in Oslo. The original wooden house has long since been torn down. His family moved there from from the small parish of Løten in 1864 when Edvard was just one-year-old.

To understand how a painting as harrowing as The Scream was conceived, we need to step back in time. Looking at present day Oslo, with its clean streets and affluent citizens, it is almost impossible to imagine the omnipresent poverty of Munch’s youth. The rising prosperity of the 1870s, which attracted people from all over Norway, had given way to steep economic decline. Life was grim for all, save the very rich. Shanty towns had sprung up on the city outskirts. Without proper running water and sewers they were breeding grounds for tuberculosis, scarlet fever and whooping-cough. Munch’s father, a devout Christian, treated many victims for free. But death was commonplace. As a child, Munch suffered TB. His mother and one sister died from it. Haunted by bereavement he painted pictures related to their deaths throughout his life.

The Sick Child 1896 Lithograph

Back on Karl Johan’s Gate, I continue west. Just before the street breaks out into an elegant tree-lined boulevard is a small square, Stortings Plass, which houses an outdoor café in summer. From 1882, Munch and some friends rented a studio there. The seated statue in the square is of Christian Krogh, one of Norway’s best-known 19th-century painters. Munch was his pupil for a time. As the most powerful of the artist’s earliest champions, Krogh bought one of his paintings to demonstrate his support. Next door to the former studio is Tostrup’s, once home to one of Norway’s leading goldsmiths. In 1882 Munch held and exhibition on the premises, after his return from Paris, where he had studied the work of the Impressionists.

A little further along on the left hand side, facing the Royal Palace, stands Stortinget, the Norwegian Parliament building. Several of Munch’s most famous views of Karl Johans are seen from this spot. One of them hangs in the shopping mall on the right, further up the street.

First, take the opportunity to pop into Grand Hotel, former haunt of poets, writers and artists. The Nobel Prize-winning writer, Knut Hamsun, was a regular client, as was Munch himself. Legend has it you could set your watch by Henrik Ibsen’s arrival each day.

On one wall is a mural by Per Krogh, son of Christian Krogh. Munch is pictured sitting at a table by a window with Hans Jaeger, a notorious libertine and radical. Here they drank and debated. They had much to debate. Christiania, as Oslo was called at the time, was a small provincial city on the fringes of Scandinavia. Norwegians were thirsty for independence from their dominant neighbour, Sweden. Talk of war was in the air. There were many strikes and demonstrations for more jobs and higher wages. Up until that point, Norwegian culture had been stuck in a romantic past that had never really existed. Pandering to the demands of a wealthy clientele, most painters depicted scenes of noble peasants in rural idylls. Munch and his circle of contemporaries began painting life as it was.

In 1882 a group of artists staged a strike against the conservatism of the Art Association Annual Exhibition. Forming themselves into the Creative Artists’ Union they exhibited in the shops of Karl Johan. Munch joined them the following year. They believed upheavals taking place out on the streets should have parallels in art and literature. Not long after, Henrik Ibsen, Edvard Greig, Knut Hamsun and Munch thrust contemporary Norwegian culture on a world stage.

Number 35, Karl Johans Gate used to house one of the largest private galleries in Scandinavia, Blomqvists. From 1902 onwards, Munch exhibited there many times.

Upon reaching Universitet Gata, I turn right, bringing me to the portals of Norway’s National Gallery. As well as Christian Krogh and Edvard Munch, works by many other leading Norwegian painters hang alongside Picassos, Braques and Monets. But, as with the Mona Lisa in Paris’ Louvre most foreign visitors go to see the gallery’s version of The Scream.

The trail is not quite over yet. Once out on Universitet Gata I wander up the street to the junction with Pilestredet. When I was there in 2002 a couple of rundown houses that appeared destined for demolition stood on the left. The most dilapidated was number 30. The ground floor windows were boarded up and covered with fly posters. Where it wasn’t sprayed with graffiti the stucco façade crumbled. Much of the roof had caved in and had been replaced with plastic sheeting. On the gable wall a gigantic black and white version of The Scream stared out. It had been painted by students of Oslo’s School of Architecture. This was the most important dwelling of Munch’s childhood from the age of three. His family and he lived there for seven years . Events that were to shape his life occurred in this very house. His mother and sister, Sophie, died there. And it was there his Aunt Karen discovered him drawing on the kitchen floor with a piece of coal.

As city councillors squabbled over whether to pull the building down for redevelopment, nature had been quietly getting along with the task of demolition itself. Finally, in 2000, a resolution was passed to preserve it. Nothing had been done, as far as I could see. Yet, while the council flustered and blustered a group of anarchists showed what could be done by opening the tumbledown Blitz café next door. Murals reminiscent of 1960s rock psychedelia adorned one wall. A pioneer of expresionism, Munch and his contempories would probably have approved, although had he painted the murals they might have been slightly less psychedelic.

More on Edvard Munch’s The Scream – doesn’t it make you want to scream

And for another cultural walk through Oslo: In the steps of Knut Hamsun

Copyright © 2013 Bryan Hemming

This is an edited version of an article first published by The Independent under the title The agony and the ecstasy on Saturday, 14th September 2002

What a fantastic, fantastic journey – and you’ve told it so well. Fancy even deciding to retrace his steps, to stand in that place with your copy of The Scream to hand. Then all that history (I didn’t know Oslo had been so impoverished), background…

Excellent read. Thank you. Well worth the read.

LikeLike

Thank you for this wonderful piece of history. Congratulations on being FP’d.

Allan

LikeLike

Thanks for your kind observation, Allan, it’s much appreciated.

LikeLike

Did you know that Munch’s Self-Portrait With Skeleton Arm (1895) was done with an etching needle-and-ink method which is also used by Paul Klee? It is interesting to me that when Munch died, his remaining works were bequeathed to the city of Oslo, which built the Munch Museum at Tøyen (it opened in 1963). Did you get to go to this Museum?

LikeLike

My Norwegian uncle and aunt lived in Sinsen, about half and hour’s stroll to the Munch Museum. I visited it quite often when I stayed with them.

I hadn’t heard the information about the needle and ink technique used in Munch’s self-portrait, and the consequent connection to Klee. It’s very interesting. Thanks for that.

LikeLike

I hope to see the Munch Museum some day myself. Thanks for sharing you blog! http://www.segmation.wordpress.com

LikeLike

Pingback: The Scream – Edvard Munch’s Oslo | ditzydelusions

This is a post of unbelievable quality. Amazing, and thank you.

LikeLike

Wow, that’s some compliment! You can’t know how much I appreciate it. And thank you too.

LikeLike

There was a great exhibition of Munch at the Tate Modern in London last year. A complex artist.

LikeLike

His entire output is extraordinary, especially considering much of it was painted in the last quarter of the 19th century.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Giuseppe Savaia.

LikeLike

To judge from a quick glance you have good-looking blog, Giuseppe, I intend to make a longer visit soon.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on KarolineDesigns and commented:

Interesting to know the story behind this masterpiece!

LikeLike

Thanks Karoline, had a look at your blog. As a trained graphic designer, I’ll be returning for a more in depth perusal soon.

Meanwhile, you might be interested in taking a peek at my photos of Conil in Spain, where I now live: http://bryanhemming.wordpress.com/wp-admin/post.php?post=1230&action=edit&message=1

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on New American Gospel! and commented:

— J.W.

LikeLike

Thanks for the interest, Jackson. I just took a peep at New American Gospel, and intend to pay another visit, after I’ve finished replying to my comments.

LikeLike

Thanks, I always wondered about the Scream- you told the story so good.

LikeLike

Thanks to you too. Munch has always fascinated me since my teens, as an art student, when I first visited the Munch Museum.

LikeLike

Wow! Beautiful telling of multiple journeys! And multiple Screams! Really interesting read! 😊

LikeLike

Oslo is a beautiful city and well worth seeing. I have been their many times, as I have Norwegian relations. I can’t wait to go back again.

LikeLike

Really, really interesting. I’ll be honest: I didn’t have time to read it all right now. But I will. I love looking back at the history surrounding the lives of authors and what inspired their work. It would be really neat to go back and walk “the walk” of an author as you did. Really well done. Although I haven’t read it word for word yet, I could tell.

LikeLike

Thanks for popping by, hope you get more time to read it fully later.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on no such thing as normal and commented:

The scream has always been one of my favourite pieces of art! It just captivates you.

LikeLike

It just says so much so simply.

LikeLike

I know the first time I saw it I was just drawn to it.

LikeLike

Well written – an amazing read!!

Look forward to reading more!!!

LikeLike

Thanks so much. Getting positive feedback makes hard work really worthwhile.

LikeLike

Your welcome!!

LikeLike

I have always loved and related to The Scream. Thanks so much for the education!

LikeLike

I realised how much people do relate to The Scream, and spent a lot of time doing research.

I’d like to mention my cousin, Terje Flaatten here, as I spent so much time using his extensive library. And also his son, Hans-Martin Frydenberg Flaatten. We spent a lot of time together visiting places in Oslo and beyond, and often discussed Munch. It proved a great help.

Those who read Norwegian might be interested in his book on Munch ‘Soloppgang i Kragerø’. You can view a few pages on this design site:

http://www.borresenco.no/soloppgang-i-krager%C3%B8

LikeLike

Reblogged this on vadercdotcom and commented:

god pics and content

LikeLike

Thanks for taking the time read and reblog. I appreciate it.

LikeLike

You are an insanely talented writer…I’m a huge fan of Munch and the intense beauty he created during his lifetime. Congratulations on being FP’d, you definitely deserve it! (:

LikeLike

Thank you . As you already know, Nicolas, I looked at your blog, and was very touched by the story I link to here: http://cultofcuriosity.wordpress.com/2013/04/12/journalism-and-the-power-of-writing/

LikeLike

Oh my! Thank you so much for this fine piece of history! I didn’t read the whole article, although the piece on “The Scream” was magnificent. Thank you very much. Impressed, indeed. I will definetley be keeping an eye out on your posts and pages!

You rock!

Parker Zinn

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed it so much. Parker, and took the time to tell me. It gives me a tremendous amount of pleasure to read people like, and get something from, my work.

LikeLike

Thanks for that in depth view of history! It was an intriguing read. Look forward to read more from your blog. Cheers.

http://vacationrentals-home.com/

LikeLike

Even more coming up very soon! I hope. Thanks for the encouraging words.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Live, Laugh, Love.

LikeLike

Thanks for that. I love your Is street art…art? piece. To answer the question posed in the title, street art definitely is art. But not all.

Some time ago I wrote an article on Granada, the Spanish city is famed for its grafitti. I link to some photos I took of it at the bottom of the piece. You can view it here: Granada

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment. I I’ll follow the link you sent, I like street art! Thanks a lot, Jona.

LikeLike

Very nicely illustrated history…

LikeLike

Thank you so much for taking the time to say so.

LikeLike

I enjoyed very much your narrative passage through the streets in Oslo , it made my mind go back 40 years ago since I am a Munch fanatic,thank you very much.

LikeLike

Glad to have inspired a bit of nostalgia. Most of the centre of old Oslo hasn’t changed so much over the years, I’m pleased to report.

LikeLike

Tussen takk.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed how you collaborated history with a sort of university-educated colloquialism-type of writing. Of course, the content of the piece itself was interesting. Furthermore, the way you depicted the painting itself with your words, in my opinion, is why you were freshly pressed. Good job!

LikeLike

And I really enjoyed writing something, which so many people have taken the time to comment on. Thanks for your kind words.

LikeLike

A really beautiful balance of personal anecdote and factual detail. I had no idea that “The Scream” was based on an actual moment on an actual bridge… despite the thing sitting on my bedsit wall for three years back at uni!

Also great to be introduced to some of Munch’s other works for the first time.

This sort of post is exactly why I like wordpress so much!

Thanks for posting mate! And congrats on the freshly pressed…

LikeLike

Thanks, Steve. I like wordpress for more or less the same reasons.

This year I hope to do some similar pieces on Spain, where I now live.

But there’s also more on Norway to come, as I have strong family links to the country.

LikeLike

The Scream is haunting in a way that the image will stay forever in your mind, as I’m sure this journey will have impact in your life as I can tell from the depth of your writing. But less disturbingly, I hope.

LikeLike

One way or another, The Scream has already made a quite few impacts on my life. The great reception this article has received on wordpress being another. Though the painting is very dramatic, it’s not though most disturbing of Munch’s works, to my mind. There are many more disturbing images revealing the darker side of Munch’s world vision.

I took a peek at your blog, and will have a longer look when I get more time.

LikeLike

Thanks for this post about Munch.

I lived in Oslo for some months and visit Munch Museum at least 10 times. Every single time I went there, I discover new things and I always tried to get more information for the next visit.

This post makes me want to go back there.

LikeLike

Glad to have inspired happy memories. It’s a great museum. I love the huge portraits, stunning! Hope to get back to Norway myself in the near future. I love it.

LikeLike

Love it.

LikeLike

Love your site too.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on thebrunettedot's Blog.

LikeLike

Very well written … I love Norway and been returning there all the time. And I like how u nicely described everything.

LikeLike

Once bitten, it’s difficult not to return. Thanks for your kind words.

LikeLike

Great post, informative and entertaining. I feel the need to return to Norway soon.

LikeLike

Having written a lot about Norway recently, I can’t wait to get back there myself.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Scream – Edvard Munch’s Oslo | uglydragon

Pingback: The Scream – Edvard Munch’s Oslo | J.D. Holiday

Thank you so much for this blog. I wrote to the Museum asking if I could have permission to use The Scream as my Gravatar for Care Of The Elderly blog but was told I would have to pay to use it so I just made another one, but I explained that this picture depicts exactly how I feel today and every day regarding my blog contents. Perhaps you may read it someday?

LikeLike

A wonderful deposition on art and travel!

This post makes me long for a plane ticket to follow those steps, and perhaps a box of crayons to create my own Shrik!

LikeLike

It’s a great walk through a great city, so get that knapsack filled with crayons and book your flight!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on TrentGalleries and commented:

Check out this article on ‘The Scream’

LikeLike

Crazy me! I’ve finally clicked back for the read and it was all so familiar. Doh, been here before. I remember this one very well, you so brought to life that scream.

LikeLike

Coincidence, déjâ vu and premonition.

Coincidentally, Pedersen considers all of these things in more depth later on in the novel. Those strange feelings when we think we’ve read something before. Perhaps you read it in a previous existence in some parallel dimension. You can never be absolutely sure. Maybe it was a premontion that you were about to read the article, or just that sinister déjà vu sensation we all sometimes feel.

On the other hand, you might’ve just read it before. The world moves in mysterious ways.

LikeLike