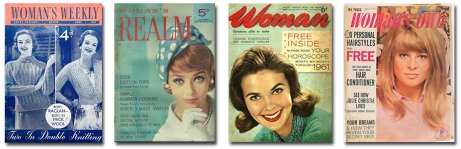

AT SOME POINT in the late 1950s, Dad ordered a woman’s magazine to be delivered to our house each Wednesday. We lived in rooms behind and above a tiny wool shop in Syston, a small manufacturing town north of the East Midlands city of Leicester. We soon learned Woman’s Weekly wasn’t worth holding your breath for. The zingiest bit was the washed-out pink and blue cover. With lots of words and few pictures the interior couldn’t compete, however hard it might have tried. It didn’t try. Things sped downhill as soon as we turned the cover. Printed in monochrome on poor quality newsprint, the joyless pages seemed a metaphor for the seemingly eternal bleakness of post-war Britain. Even by the austere standards of those times the periodical appeared dowdy and dated. Costing fourpence, in pre-decimal coinage, it arrived with Wednesday morning’s newspapers, looking so weathered it might’ve been lying on the doormat since the Great Depression.

AT SOME POINT in the late 1950s, Dad ordered a woman’s magazine to be delivered to our house each Wednesday. We lived in rooms behind and above a tiny wool shop in Syston, a small manufacturing town north of the East Midlands city of Leicester. We soon learned Woman’s Weekly wasn’t worth holding your breath for. The zingiest bit was the washed-out pink and blue cover. With lots of words and few pictures the interior couldn’t compete, however hard it might have tried. It didn’t try. Things sped downhill as soon as we turned the cover. Printed in monochrome on poor quality newsprint, the joyless pages seemed a metaphor for the seemingly eternal bleakness of post-war Britain. Even by the austere standards of those times the periodical appeared dowdy and dated. Costing fourpence, in pre-decimal coinage, it arrived with Wednesday morning’s newspapers, looking so weathered it might’ve been lying on the doormat since the Great Depression.

Nights on the Arctic island of Værøy had me tossing and turning to memories of my childhood for hours before finally dropping off. There were good memories and bad. With Dad gone a few years before, unpleasant things needed confronting. Not confronting them would mean continuing the public face of the good and decent parent my sisters and I had helped him foist upon friends and family alike. A myth we had continued to perpetuate long after his death. There had been the sort of omertá that accompanies most funerals; the unspoken mantra you mustn’t speak ill of the dead. Not that anybody says that about Adolf Hitler or Pol Pot. If nothing else, for peace of mind, I had to put things right in my own head.

Though vaguely aware something was wrong, throughout my teens and well into my twenties, I learned to push the more unpleasant memories of the past to the farthest recesses of my mind, where they were left to fester among the shadows of half-forgotten dreams and nightmares. On the rare occasions one or other would drift back, I would shut them out. But prompted by Dad’s departure, they had began to re-emerge with growing frequency. The gnawing guilt some of my recollections incited had me questioning their veracity. I felt I could no longer trust my memories, in spite of the fact my sisters’ recollections bore witness. Truth was, I hadn’t wanted to remember; it was too uncomfortable and too humiliating.

Decades later, inexplicable feelings of guilt still stalk my subconscious on a daily basis. At times, the dull ache devouring the pit of my stomach, reaches up to pull at my heart. Plagued by dark thoughts I was now struggling to find sleep on a small island off the northern Atlantic coast of Norway.

Dad’s logic for subscribing to Woman’s Weekly was the magazine’s featured knitting patterns. Not that any of us dared ask. Dad just felt it necessary to explain why a man might order a woman’s magazine. It’s the sort of conundrum young boys don’t think about until somebody puts it into their heads. Took me some time to work out it might have something to do with the fact Dad’s shop sold wool. My three sisters and I knew he wasn’t an avid knitter. At least, I can never recall him sitting down with a pair of knitting needles and a ball of wool. I can’t remember him reading the blessed magazine either. Blessed, that was a word Dad often used. He pronounced it bless-ed. And he didn’t mean things or people were actually being blessed, like in “bless-ed are they who hunger and thirst for righteousness”. For years I laboured under the impression Jesus was cursing the meek and poor in the Beatitudes just for being meek and poor. If Dad did ever read the bless-ed Woman’s Weekly he must’ve done it beneath the bedclothes by torchlight. His idea had probably been for Mam to keep abreast of wartime knitting fashions for woolly hats with pom-poms, and sleeveless, Fair Isle pullovers for small boys, tight enough to severely restrict comfortable breathing. Every other mother in Syston seemed to be keeping up, despite the war having ended more than ten years previously.

In the days before TV became widespread, it was fairly common for many British households to have two, or even three, newspapers delivered each day. Including the late edition of the Leicester Mercury, Dad took three most days and four some days. On the three days a week he worked properly, Dad sold skeins of woollen yarn and nylon stockings from a stall at Coventry market. Towards the end of each Saturday afternoon, he would reach into the cash tin for a few coins before sending me running after an ambulant newspaper vendor breezing through the city centre, crying something that sounded like “E’eee…tereh…grawah! E’eee…tereh…grawah!” Dad took the Coventry Evening Telegraph sports edition, or the Pink un, as it was known for the colour of its paper, to check the football results. If he’d predicted the eight score draws needed to scoop up the £75,000 jackpot on the pools, he’d never have to work again. Not even three days week, for the rest of his life. He never did. Win the pools, that is

By Wednesday, it seemed winter was already returning to the Arctic. August had only just begun. Though the sun came out, a wintry wind blowing beyond the shelter of the fisherman’s huts had me pulling up my jacket collar. Were it not for the discovery of how to turn the heater on, I might’ve considered heading back south. My fingers had been getting so cold it became impossible to work at the keyboard for long periods. With the radiator on I could write for much of the day. The rough first draft of my novel Pedersen’s Last Dream was nearing completion. Despite feeling a bit lost on starting again, I kept chipping away, picking up threads again as I went. Leave a work too long and you have to go right back to the opening; a journey I’d already embarked on too many times.

No sooner had I mounted the bike to get a loaf of bread than I heard Agnar call out. He stood by his hostel entrance, contemplating the impossible tangle of rusty handlebars, frames and wheels, stacked against one wall, that comprised his bikes for hire. Scratching his head, he appeared like a man desperately searching for an excuse to do something else. I provided the diversion he needed. He asked me where I’d been over the weekend. On an island less than five miles long, dominated by a spine of rugged mountains, it seemed an odd question. There were only three likely locations I could have been, here, there, or over there. Assuming another motive to the question, I told him I’d pay the rent I owed later in the day. Shaking his head slowly, it appeared something else had been on his mind. It may have had something to do with the shambolic state of the ancient two-wheeled wrecks he rented out. Weighing up the odds, sooner or later, someone was going to have a very nasty accident. He could’ve been thanking the Lord he’d been lucky again. He might easily have lost a bike. There are a lot of sharp mountains from which to tumble on Værøy, and a lot of turbulent ocean in which a bike could disappear without trace. Keeping a wary eye out for his property, he told me he’d noticed my particular bike hadn’t been leaning in its customary position against the wall of the fisherman’s barrack for the past few days.

Before setting off for school on winter mornings in Syston, I would often stand, staring out of our misted shop window. Concealed behind a display of plaster half-legs clad in varying shades of nylons with names exuding luxury, like Bermuda, Light Tan and Mink, I would gaze transfixed at the procession of grey silhouettes of grey men in grey raincoats, grey jackets, grey trousers and grey flat caps, gliding through freezing grey fog on grey bicycles. Stacked behind the plaster legs were half-open brown paper packages revealing multi-coloured hanks of knitting wool I could peer between. Were it not for their motion, the riders would have been virtually indistinguishable from the overwhelming greyness forming a veiled backdrop of grey houses and grey shops belching grey smoke from grey chimneys. The seemingly reluctant procession was headed to Etough’s shoe factory in Broad Street, or one of the other small factories and workshops situated near and by the brook. Grey against grey. Most riders puffing at the untipped Park Drive or Woodbine cigarettes glued to their lips, it was easy to imagine the bikes being driven by coal-fired steam. Their nicotine-enriched exhalations augmenting the fog, the grey men pedalled their machines as silent as ghosts, apart from the gentle ticking-ticking of the three-speed Sturmey Archer gears, and the muted murmur of rubber on asphalt.

Idle chat no longer coming easy, I didn’t tell Agnar I’d spent a good part of the weekend slurping cans of beer at the old schoolhouse in the abandoned village of Måstad on the other side of the island. Turid and I had left our bikes unattended by the quayside before boarding Paal’s motor cruiser for our drunken excursion. My reluctance to tell didn’t spring from the idea it didn’t fit the ‘need to know category’ but from the realisation getting out the necessary Norwegian to explain would surely hurt my head. Besides, he would almost certainly garner the full story from the island grapevine.

Copyright © 2015 Bryan Hemming

“Leave a work too long and you have to go right back to the opening; a journey I’d already embarked on too many times.” No truer words have ever been said.

This could be your grey and pick post. Grey goes well with pink….

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s funny how dark thoughts seem to recede and reappear at random. Psychological abuse is so difficult to heal. Scars need to be located before they can be healed. And how they love to evade.

So true about having to start again at the beginning if you abandon a work for too long. I could feel the loneliness of that cold, mountainous island. A perfect place to write, really.

LikeLike